Bernhard Leitner -- EARSPACEBODYSOUND

“I can hear with my knee better than with my calves.” This statement made by Bernhard Leitner, which initially seems absurd, can be explained in light of an interest that he still pursues today with unbroken passion and meticulousness: the study of the relationship between sound, space, and body. Since the late 1960s, Bernhard Leitner has been working in the realm between architecture, sculpture, and music, conceiving of sounds as constructive material, as architectural elements that allow a space to emerge. Sounds move with various speeds through a space, they rise and fall, resonate back and forth, and bridge dynamic, constantly changing spatial bodies within the static limits of the architectural framework. Idiosyncratic spaces emerge that cannot be fixed visually and are impossible to survey from the outside, audible spaces that can be felt with the entire body. Leitner speaks of “corporeal” hearing, whereby acoustic perception not only takes place by way of the ears, but through the entire body, and each part of the body can hear differently.

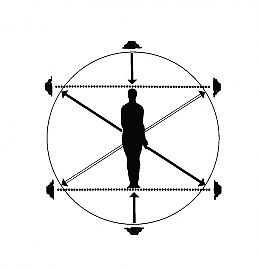

Bernhard Leitner is considered a pioneer of the art form generally referred to as “sound installation.” He introduced sound to the installation space, allowing the installation space to emerge through the sound. Leitner, who actually studied architecture, has been a visionary ever since the very start of his artistic career. His sculptures—which he refers to as “sound-space objects”—and installations are the result of long, complex processes of development. In precise sketches and workbooks, he first approaches the sculptural, architectural qualities of sound in theory. He undertakes, as it were, foundational scientific research by studying frequencies, volumes, movements and combinations of sounds and their impact on the body, sketching possible spatial figures, such as cubes, corridors, fields, pipes, and exploring the impact of bodily posture on acoustic perception. In 1968 Leitner moved to New York, where he concretely began working on sound-space studies in his studio. He developed multi-channel compositions using sound recordings that were not musically conceived, from which he extracted specific sound material and combined it in work-specific series of sounds. He then notated these series using visual codes that he himself developed consisting of letter combinations on rolls of paper, and transferred them to perforated tape. This resulted in temporary installations of wooden slats on which loudspeakers could be arranged in various geometric arrangements. These were operated individually by way of a control device developed together with a technician, for this was not possible with devices found on the market with the then current state of technology. In this way, Leitner was able for the first time to place sounds and series of sounds in various, exactly performed movements that create “spatial models in an invisible (new) geometry.”1 As Boris Groys has argued, the visual formulation of Leitner’s installations can be read in the tradition of the aesthetics of New York minimalism in the 1970s. There are echoes of Richard Serra, Carl Andre, or Donald Judd, even if the reduced and strict formal language of Bernhard Leitner enters into a new functional context that “serves to shift attention from the visual to the acoustic level of the installation.”2 In the moment when the visitor is no longer unnecessarily distracted by visual stimuli, acoustic attentiveness automatically increases.

Bernhard Leitner’s exhibition EARSPACEBODYSOUND at Georg Kargl Fine Arts represents in several aspects something quite special and also a challenge. His first extensive show in Austria in almost ten years, this exhibition is also his first gallery show worldwide. Independently and uninfluenced by the art market, Leitner developed his own “universe,” his own space of thought, which found widespread international recognition on an institutional level. He participated in Documenta 7 in 1982 and the Venice Biennale in 1986, and has also been able to realize numerous sound installations over the last forty years in public space, for example the Agoraphon in front of Hamburg’s Deichtorhallen in 1994, or Cylindre Sonore from 1987 at Paris’ Parc de la Villette (still extant today) or the Strömungen (Streaming) at the orthopedic division, Otto Wagner Hospital, Baumgartner Höhe, Vienna (Felix Pavilion), in 2000.

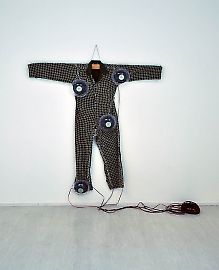

The current exhibition focuses primarily on the complex process of development behind the Leitnerian sound/space/body web of relations, pursued with such amazing meticulousness. It attempts to provide both a historical retrospective and to sketch out current positions. Alongside historical documentation material such as work and notation and sketch books, the exhibition includes early sound sculptures like the Tonanzug (Sound Suit, 1975), the Tonliege (Sound Chair, 1974/1983) or Tragraum (Portable Space, 1976) that are committed to the “modern principle of the emanative body”3 to the extent that sound palpably influences the entire vegetative nervous system through loudspeakers directly worn on the body, allowing it to become a whole body experience. Leitner thus stands in the tradition of the international avant-garde movements of Fluxus and Happening, which expanded the concept of art by including the human body in the artistic context. The passive viewer becomes an individual agent in the artistic process, an element that is inseparable from the artwork in that his or her role as the beholding subject shifts to that of the object beheld. While the Sound Suit or the Portable Space allow for the user’s individual movements, that is, the user carries the sound around, and depending on the position or distance from the surrounding space also actively shapes the individual spatial experience by way of reflection or feedback, installations such as Pulsierende Stille (Pulsating Silence, 2004), Vertikaler Raum (Vertical Space, 1975) or Klangspiegelgang (Sound Mirror Path, 2011, created especially for the current exhibition) assign a clear place to the visitor. The experience of most of Leitnerian sound space sculptures is a subjective, lonely matter. Group dynamic collective experiences are shifted in favor of meditative interior examination, in that the visitor becomes aware of his own body belonging to the unified space of the sound installation. In so doing the transitions from “space-feeling (in architecture)” to the “feeling space (of music)”4 begin to blur.

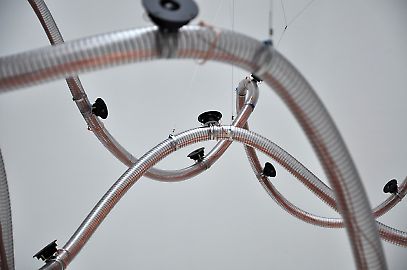

The extent to which Leitner’s installations are not only able to decelerate or subdue the movement of the visitor, that is, his or her form of reception, but also to dynamize it, is impressively shown in the 48-channel composition Serpentinata located in the gallery’s skylight space. Through two plastic tubes, which are tangled with one another, hanging organically free in the space, with 24 loudspeakers placed on each of them at regular intervals, the sound seems to drizzle down, making a crunching noise, sounds that seem to shoot through the space, hissing, transforming the entire sculpture into an “acoustic-resonating organism” (B. Leitner) that almost seems to breathe. In comparison to the reduced, formally ascetic installations in which the sound series seem to span geometrically meticulous spatial bodies, Serpentinata seems like a lofty, sanguine spatial inscription that the visitors try to follow in almost dance-like movements.

In recent years, Bernhard Leitner’s sound/space/body installations, that have always developed at the intersection of sound, sculpture, and architecture, refusing any clear location, have begun to attract the interest of artists from the performing arts. Dancers and performers develop their own choreographies along Leitner’s sound/space/bodies and allow new corporeal and movement spaces to emerge in temporal-spatial performances. They allow themselves to be drawn into a universe in which visual, acoustic, temporal, and physical worlds of experience “coincide,” and “being in sound” becomes a “being in the world.”5