Raymond Pettibon -- Zeichnungen der 80er Jahre

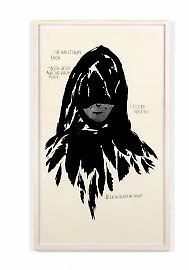

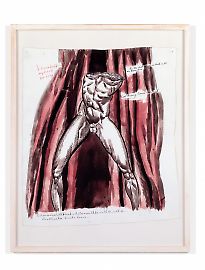

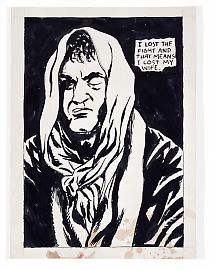

[…] Pettibon’s work sees the murder of Sharon Tate by the followers of Charles Manson, and the Altamort concert of the Rolling Stones—where the Hell’s Angels, taken on as guards, killed a black member of the audience— as having marked the all too precocious collapse of the high-flying hopes and demands of the generation of 1968. Pettibon’s work speaks openly of this debacle and pairs it with often frightening images, and in doing so it offers a striking example of how an artist from the underground has been able to become an acknowledged representative of so-called high culture. […]

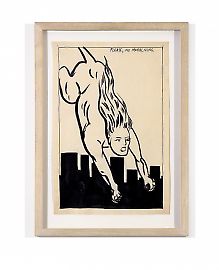

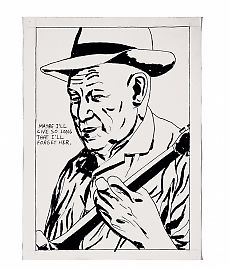

A real understanding of the references and background of Pettibon’s [works[ demands considerable of knowledge of the social and political landscape of the United States in the course of the last forty years: a knowledge of the major stories which the media in this period of time have reported, and made a part of the field of awareness of the average American: but also a knowledge of the culture of day-to-day life in the United States, and an acquaintance with many such groups as the California surfers and hippies of the 1960s and early 1970s. The viewer of Pettibon’s works must know such names and personalities as Charles Manson, Sharon Tate, Patty Hirst, “Lady Bird” Johnson, Lee Harvey Oswald, and many more, and be aware as well of the look of the faces they bear or bore. The viewer has to know the music of The Grateful Dead, the texts of various songs, certain comic strip figures and film personalities, simply for a basic understanding of the context to which Pettibon refers. […]

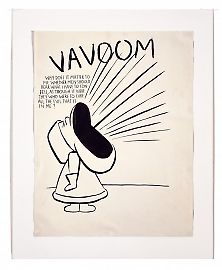

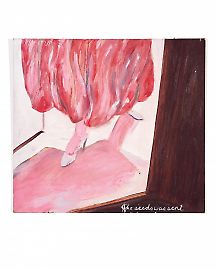

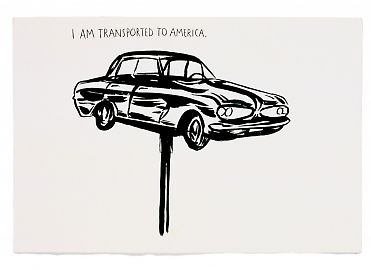

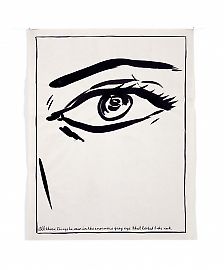

Comment is also repeatedly made on the relationship between Pettibon’s work and drawings of William Blake, the nineteenth-century English visionary whose depiction of the war between heaven and hell relied likewise on combinations of image and text. […] While playing with the clearly and simply structured work of comic strips, Pettibon’s works cannot themselves be said to belong to it. It’s precisely its departure from the regularity of the professional execution of comic strips that indicates the distance between the content of Pettibon’s work and the visual sources to which it intentionally refers. Quite differently from typical comic strips, where text and image more or less mechanically interrelate, now the one, now the other, developing a linear storyline, image and text in Pettibon’s work establish an often irresolvable tension. At first glance, and if only because of representing some well-known object, the image has a touch of something clear and obvious, but that clarity is sure to go astray on taking a second or third look. One stands quite clearly here in a realm of conundrum and dissociation, elevated to a principle of construction. […]

Pettibon’s […] motifs and themes […] have something of the character of a stock of apocalyptic imagery. […] The differing variations on any given theme can likewise be combined with entirely different texts that have nothing to do with one another. This is especially so for the themes that recur with the greatest frequency: the speeding car and trains, Stalin, the burning cross, the Bible.

Andreas Hapkemeyer, “Raymond Pettibon: The Pages Which Contain Truth Are Blank,” exhibition catalogue, Raymond Pettibon: The Pages Which Contain Truth Are Blank, Museion–Museum für moderne und zeitgenössische Kunst, Bozen, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, Skarabæus, Innsbruck 2003, pp. 68-87.