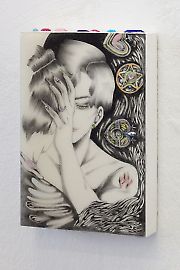

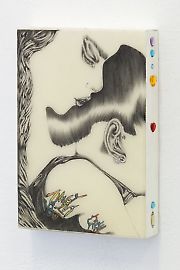

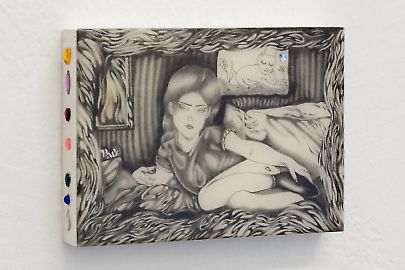

LISA SIGNORINI -- All magic comes with a price | Curated by Alexandra-Maria Toth

Lisa Signorini, All magic comes with a price | Curated by Alexandra-Maria Toth, Ausstellungsansicht, 2022

Lisa Signorini, All magic comes with a price | Curated by Alexandra-Maria Toth, Ausstellungsansicht, 2022

Lisa Signorini, All magic comes with a price | Curated by Alexandra-Maria Toth, Ausstellungsansicht, 2022

Lisa Signorini, All magic comes with a price | Curated by Alexandra-Maria Toth, Ausstellungsansicht, 2022

Ausstellung: 15. Jänner – 31. März 2022

Psychologically speaking would only ever be a second-order commentary on whatever the psyche has to say. The psyche, Psyche: the beautiful female that inhabits us all, the Daddy’s Girl, the Dumb Blonde.[1] Psyche is the observer incapable of observing her own observations, which is why we all want to be like her. Sadly, we can only reckon with her through language and narrative, and yet her story reads quite implausibly. Faced with the wrath of Aphrodite, Psyche must undergo four seemingly impossible tasks to atone for a forbidden romance. It is surely some feminine quality that ensures her success. Nevertheless – or, therefore – she is not happy, she doubts her own supernatural abilities. Psyche’s “imposter syndrome” might be considered one of her feminine qualities, depending on our ideas about mortal women in the world, in the underworld or among the gods. Still, this never touches upon anything real.

Psyche is as psychic does. The psychic is a figure who aspires to mysticism in her working life. She labours under the illusion that unrelated events are causally interconnected. The candles are flickering, the dead are communicating through the palms of her hands. She believes that her personal thoughts can influence an external world, that resemblances equate to more than mere coincidences. But I’m speaking psychologically here, with an ego blinkered by its dream of intactness, wholly convinced by a pregiven testimony of reality. The psychic’s moments of genius, however, are ineffable, noetic in quality, transient and passive.[2] They defy the rational mind, pierce its filter and let the recognisable – the self – flow out into the inexplicable – the other. The price is dissolution, the end of autobiography, the acknowledgment that the world has no centre. The fare covers a return trip to the underworld and back, after which we will never be the same again.

We choose to disbelieve Psyche because she conflates matter with spirituality, we disregard the psychic because she intends something too strongly with her mind. We presume that Psyche is hiding something, repressing some Ur-Sache that would unpack the symptom of her pathological lies. Such a presumption, however, fails to engage with the cultural preoccupations that produce psychic illness: the fact that Psyche is so beautiful that we cannot refrain from picturing her, posting her, sharing her, idolising her, shaming her. Why not sketch out her likeness in graphite and watercolour, wait for a certain alchemy to turn the image from self-knowledge towards collective madness? Diagnoses have only ever described the way we respond to the irrationality of society-building, the excess of being that gushes out when morality bites on the clitoris, when the Other is chained up in the shadows. Hysterical woman, multiple-personality-disorder woman, Influencer woman, narcissist, freak. She tells her fanciful stories and her payment (the price, the fare) to us has the function of neutralising something infinitely more dangerous than money.[3]

Miriam Stoney

[1] See: Andrea Long Chu, Females (London: Verso Books, 2019).

[2] See: William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1902).

[3] Jacques-Alain Miller (ed.). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan. Book II: The Ego in Freud's Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954-1955, transl. Sylvana Tomaselli. (New York; London: Norton, 1991), p. 204.