Muntean / Rosenblum -- How Soon Is Now

The pictures of Muntean/Rosenblum are characterized by references to the way we perceive things today, which is influenced by the media, advertising, film and popular culture. Their pictures reflect TV frames as much as they refer to comic strips or “the art director’s gaze“. At the same time Muntean/Rosenblum consider their art to engage with themes from the history of painting and art. Their figurations are modeled after lifestyle magazines such as ID, Face, Vogue etc., which provide the stock of compositional elements and figures they use. These belong to a lifestyle-oriented society where youth is a marketable commodity and “being young” has become an instrument of permanent self-control. The magazines cooperate with specialists in affective image production, appropriating forms that used to stand for protest, utopia and delimitation, as well as allegorical themes and subjects from art history.

The paintings and drawings by Muntean/Rosenblum visualize what the art historian Aby Warburg identified i.a. in the “formulas of pathos” (visual representations of heightened emotional expression) he researched: the same gestures may have contrary meanings in different epochs even though that which constitutes the individual event becomes something objective and permanent. For example, a gesture reminiscent of the Deposition from the Cross is found in a lasciviously curled-up youngster full of apathy and boredom in a Muntean/Rosenblum work. These figurations charged with art history are combined with various kinds of backdrops. Usually, these are landscapes from the suburbs, expressways, parking lots or interiors with TV sets, barstools and disco balls. The subjects are brought together with strange lines of text or statements reflecting seemingly individual or societal issues while at the same time creating some sort of surreal or banal disconnectedness. Similar to texts composed of letters in different typescripts, the figures in the polychromatic acrylic paintings look as if they were cut out of different contexts and copied into a new framework.

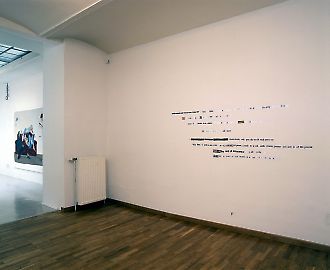

All in all, the pictures are somewhat “brand”-like or conceptual. There are various series characterized by the same underlying pattern, always showing new representations of youthfulness, and thus reminding of the serial inventory of an unknown species documented and examined in its medialized appearance. Due to this and the fact that the models are charged a semblance of authenticity, one might jump to the conclusion that this is supposed to be “the portrait of a generation”. However, by using various alienating effects in their composition, Muntean/Rosenblum create contradictions and ambiguities. Next to the easel paintings and drawings, the installations, videos, objects and photographs look like parts of a “making of” documentation by Muntean/Rosenblum. They include the treadmills of fitness studios, the interior architecture of fast-food chains, as well as the façades of prefab houses, popular dwellings of modern consumer culture. The spaces in front of and within these sterile settings are populated by those who portray young people, sometimes even wearing T-shirts of the Muntean/Rosenblum “brand”. The medium of painting and drawing pops up here and there on the various stages, disengaged both scenically and cinematically.

Their new video work “It is never facts that tell “ contains no traces of civilization or societal context. The performers are standing or moving about in a barren, dump-like hilly landscape, looking like the disciples or followers of a spiritual community. The camera frames show monumental views of the sky with flocks of birds and dramatic cloud formations moved around by the wind to a sound track of elegiac baroque music. The performers move through this scenery like pilgrims in a weird and absurd procession. Instead of the pictures of saints or icons they carry boards or protest signs and a flag with illegible lettering. The voice-over construes the “we” of a generation, a group that is insecure about certainties and ideals, stuck in a kind of timelessness and mulling over the continual return of the same and the exchangeability of values. The appearance and clothes of the performers conforms with the typical looks of youth culture; by contrast, the cinematic mise-en-scène is reminiscent of imagery used to depict various kinds of religious and pathetic themes. In their artificial stagings, Muntean/Rosenblum investigate the esthetic construction and potential instrumentalization of pathos devoid of meaning.

In the context of Muntean/Rosenblum’s focus of work, the question arises as to whether certain forms of design and architecture could also be termed “formulas of pathos”, and if so, whether they are equally prone to radical re-readings. One thing is sure: the design of Russian constructivism, which is part of Muntean/Rosenblum’s new works and used to be closely linked with revolutionary political ideas, has long become integrated in the fashionable contexts of conventional culture. Similar to the formulas of pathos in visual art, the constructivist designs of Tatlin, Lissitzky or Rodchenko are characterized by drama and theatricality, too. This is the “pose” of activism Muntean/Rosenblum are interested in.

When we consider the paintings and drawings by Muntean/Rosenblum as objects of study, we will find that youthfulness is to a great extent communicated by gestures of being an outsider, reflecting skepticism, boredom, ambivalence, lasciviousness, self-contemplation or provocation. These gestures of egocentricity and detachment create something a last remnant of “authenticity” and credibility – a scarce commodity in the cynical world of advertising – which is the reason why they are specially suited for advertising various lifestyle products./ However, what happens to these gestures in the compositions of Muntean/Rosenblum is something different: by transferring them into the context of painting, they boil down to something timeless, general, and indeterminate. The gestures are released from their contexts, they look a little lost when they stand for themselves only, and they suddenly appear to be individual modules taken out of a context that may have been allegorical or art-historical. This equivocality, the feeling of remembering something without being able to say what it was, is precisely what lends these pictures their appeal and a strange incompleteness.

Cosima Rainer 2004