Denisa Lehocká -- POINT

Never Not Urgent:

Taking respite with the work of Denisa Lehocka

By Maria Hlavajova

There is an object on my desk that I cherish tremendously. Whenever I need respite from the grueling, ceaseless flow of work, even if for a nanosecond, my eyes try to rest on it so as to soak little bit of energy and trick my mind to power forward against all odds . . . against perpetual exhaustion, against ridiculous demands, against pressing deadlines, against all things life—just like now.

The object in question has no title, or is at best named Untitled, as is customary in Denisa Lehocká’s work, but, honestly, I just don’t know. Neither am I sure when it was made or when she gifted it to me; it could have been anytime over the last thirty-plus years, throughout which she has been systematically and unwaveringly engaging in her work and which correspond roughly to the time we have known each other. This seems not insignificant—I mean, the fact that I cannot quite put a name and date to the object—for these labelling tropes of (western) art history, which routinely divide an ongoing practice into distinct works, or cast nascent explorations into isolated timelines, or break the flow of engagement into unrelated projects, might be of no consequence here. None of this applies. The said object could have been withdrawn, temporarily, from any of Lehocká’s installations, and, equally, it could be plugged back into her compositionist formations at any point, as they evolve in time. Just to be sure: this is not to say that the object is anonymous by any means, is interchangeable, or does not matter. On the contrary, the thing is of Lehocká’s oeuvre, and is unmistakably so. It belongs to her continuously emergent inquiry—an unending, enduring, incessant flow of exploration—not into individuated objecthood nor merely into what we simply call “art” but into the possibilities of living livable life otherwise than what we “know.”

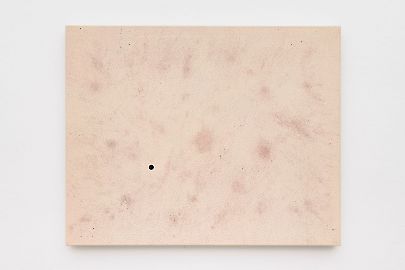

The object I am talking about, of elongated shape—ovoid and phallic at once—is covered in hundreds, maybe thousands of tiny white beads. The beads are connected with one another and the substance beneath them with a white thread, which has—likely with the passing of time—changed its hue ever so slightly. It might be that it is this shifting shade that gives away the inside of the object, as it seeps through the few patches in between the pellets. Strangely, this inner physique, an amorphous body of sorts, seems to consist of the very same thread, albeit tangled and turned around itself millions of times. A yarn coiled and tousled and twisted until it not only holds its shape, both soft and firm, but also—in ways I cannot quite explain—holds space for my rest and at times for my thinking and my feeling.

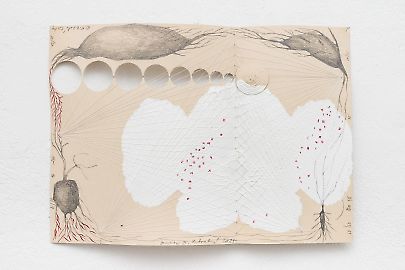

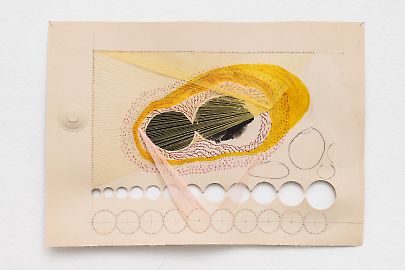

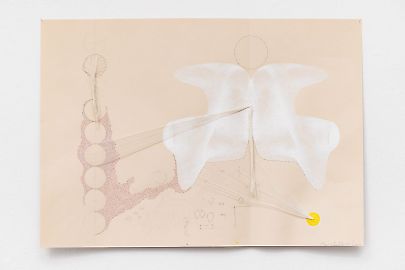

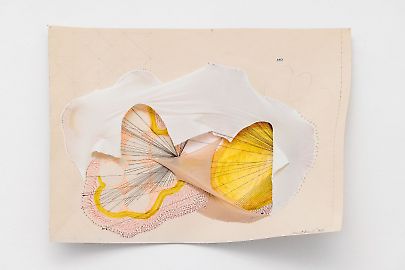

I cannot quite fathom the amount of labor that went into this. The amount of ceaseless flow of work, not unlike that which I seek to break from when I stare at it. And that’s merely this one tiny thing. Just think of the sprawling installations of myriad alike elements that Lehocká composes together. With every object added, with every bead sewn in, with every string or cord tangled and snarled, with every new drawing drawn, with every embroidery needled, with every pearl glued to the piece of paper or twig or gauze or stone, with every form of plaster or clay molded, with every connection secured with a rope to hold all above together as equals, in balance and in relation . . . think about that labor.

Just why does it feel so different from the exhausting toil I seek to escape?

“As women,” feminist writer Audre Lorde once said, “we need to examine the ways in which our world can be truly different.”* Quite an ask, for as we drag through reality of which the “principal horror” is that it demands everything from us. We are emptied by its extractive logistics that feed on our capacity to live fulfilling lives and our capacity for joy and our capacity for love—love for work included. Berobbed and left disaffected “from so much of what we do,” where do we turn for “that sense of satisfaction and completion”? For that vital sensation of “fullness”?

“As women,” Lorde again, “we have come to distrust that power which rises from our deepest and nonrational knowledge,”* and that power is the power of “the erotic.”* Not that superficial thing at times mistaken in the men’s world for pornography, but the erotic as a source of power stemming from the deeply embodied knowledge one needs to reclaim from the way of the world today. The erotic as a question not merely “of what we do” but “of how acutely and fully we can feel in the doing.” “When I speak of the erotic,” says Lorde, “I speak of it as an assertion of the lifeforce of women; of that creative energy empowered, the knowledge and use of which we are now reclaiming in our language, our history, our dancing, our loving, our work, our lives.”*

And there you have it. The object on my desk, and per extension the work of Lehocká in its entirety, seems to stem precisely from the inner knowledge that only by systematic circumnavigating of the external directives and expectations—of what next urgency we must respond to, of what we do and how and when and with whom, of what the works of art must conform to—that “we begin to be responsible to ourselves in the deepest sense.”* The innermost power of the erotic at play here is to devote energy and labor not to the questions and pressures of and by the dominant order and the powers that be, but to the questions and yearnings of our own.

Those yearnings pursued in Lehocká’s work, then, embody a stubborn insistence on joy in work and in life, against all odds. It gives form to the understanding of and being in resistance to the world of exploitation. It is a refusal, both subtle and radical, to submit to perpetual exhaustion, to ridiculous demands, to pressing deadlines, to all things peripheral to the true meaning of life.

When in her studio, that stubborn and gratifying, committed and steadfast flow of Lehocká’s work goes into the patient, slowly unfolding, laborious connecting of the myriad tiny particles together into objects, and then the myriad objects into larger ones, and then those compositions into even larger formations. When brought out of the studio to become public, the work’s ethos of connecting implicates us all in it—by insisting on us to recognize our mutual interdependencies. It is, in fact, an act of sharing with others—of art and of labor—the proposition that another work, another us, and, thus, another way of life is possible. The act of sharing “the power of each other’s feelings,” to put it in other words, and, following Lorde, of the possibility to together “pursue genuine change within our world.”*

That the said object by Lehocká ended up on my desk, then, is no happenstance but the conscious act on the part of the artist to share with me in this energy and these beliefs. Whenever I am in need to borrow from this electrifying offer, I know it is not so to continue the daily grind expected from me but rather—entrusting that one is not alone but connected to others dealing with the same dilemmas—to excavate from within the world at present the potentials of a collective livable life, otherwise.

It is this celebration of the erotic in Lehocká’s work that, in spite of the world, is never not urgent.

Edited by Aidan Wall. With thanks to Rahel S. and Peter K.

*Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power”: Fourth Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, Mount Holyoke College, 1978.